Born Anew: Heritage Grape Varietals in a Renaissance Period

Written by Ella Smit, in conversation with Alfie Alcántara & Deanna Urciuoli

Dear Native Grapes is a project born from the desire to pay homage to Vitis Labrusca varietals, America’s forgotten heritage grapes. We sat down with Alfie Alcántara and Deanna Urciuoli to discuss their ambitions for their vineyard broadly in the world of wine.

Ella: You both come from the film industry, which is not directly related to the wine industry. How did you arrive at winemaking and your venture into entrepreneurship?

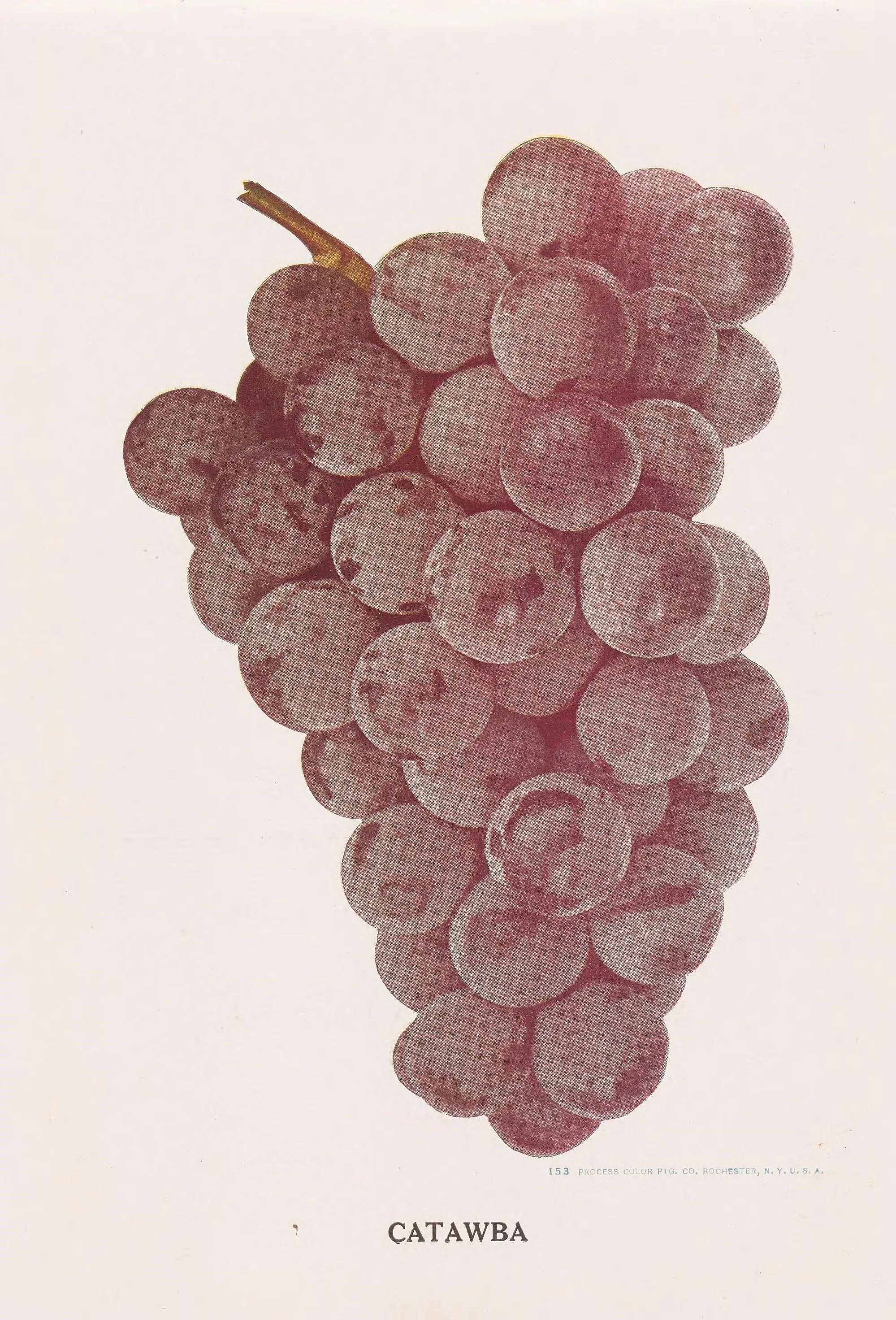

Deanna: New York City is where we first started getting into natural wine and going to natural wine bars. We started going to “June” and talking to the bartender about what new wines were coming in. They were teaching us about new varietals that were native to different countries around the world, such as Georgia, Spain, and the Azores. Learning about these varietals and the different palates they offered sparked questions about which grapes were native to America. Not many people were talking about native American grapes, at least we weren’t seeing these varietals on menus with any kind of frequency. Alfie did some sleuthing to understand the history of heritage grapes that were suited to our climate, disease resistant, and cold-hearty. Every day, he would resurface with new learnings.

Finally, Alfie mentioned doing a farm project as a vineyard project, which made sense to us. It was the coming together of different passions. Ignorance is bliss, and that’s how we felt when we first set the course. Alfie was excited and persistent that this could be a great vineyard project.

Alfie: Deanna encouraged me to start volunteering at vineyards and continue learning. She’s the planner and logistics guru, so she put us on a savings plan towards a down payment on farmland. I started reaching out to small natural wine producers to learn more about the business. I appreciate that practical side of her. I was volunteering at Wild Arc Farm in the Hudson Valley where I met Todd Cavallo and Crystal Cornish, who became mentors of ours. They’re so generous with their time and knowledge and open to sharing that with people who are interested in agriculture. In the meantime, we started taking online small-farm business courses through Cornell, which pushed us to think through our business plan very intently. We needed the project to be sustainable for our family someday and a source of income.

Deanna: Alfie’s an artist and a dreamer, which is very prevalent on his side of the family. Planting the first few steps is hard, but that’s what we had to do. Originally, we weren’t sure where this project would take place. I wanted to stay in New York State. Alfie floated going to Colorado, where he spent many of his formative years, but it would’ve been a vastly different project. Our community, friends, and family were in New York.

Alfie: We ultimately arrived at Delaware County, the western Catskills, where the real estate prices were attainable. The land is very bucolic, with rolling hills and farmland. We wanted to cut through the bias of these grapes and where they could be grown, which was a looming challenge.

Deanna: There’s a very strong agrarian history, particularly among dairy farms in Delaware County. It’s still prevalent today. It’s also the watershed for New York City. We set our sights here and did a few true-to-form viewings. We landed on the first place we looked at. The hillside was perfect for grape-growing, with southeastern exposure and fog rolling right off the hillside. We did soil tests as well, which came back as being high in organic matter. The previous farmer hadn’t sprayed but rather grazed cattle and other animals.

Alfie: We were able to buy the land in the fall of 2019 with the idea that we were going to do this slowly. Initially, we wanted to work on the house and plant a few rows of grapes to see how they’d fare. Obviously, the following spring was the start of the pandemic. Our work situation was really impacted. I’m a freelance camera-man, so I was out of work. Deanna was able to work remotely for her full-time job. We put our energy into starting the project because we had the time. We DIY’d the house based on YouTube videos we watched to be thrifty about it. All throughout that year, we worked on the house before we turned our attention to planting vines.

Deanna: [Initially] we planted 3-3.5 acres because we had the time and ability to cultivate the property. It was last minute, but we worked with a few nurseries to get some vines and cuttings. Family and friends came up to help us figure it out. We had to identify how to plant the rows, measure the spacing and field, and map the land to create a schematic to understand how many vines we could feasibly plant. We wound up putting in 21 rows that first summer; it was a true friends and family effort during the lockdown and done in shifts. We were thrilled to see the vineyard come together in 6-months with 2,000 vines taking shape. We’ve since expanded with two more plantings: one in 2021 with 10 rows and again in 2022 with 12 more rows. In total, we have about 44 rows.

Ella: I’m drawn to your interest in storytelling and acting as conduits to revive a forlorn history of winemaking in the Catskills, and how that’s largely been obscured from our cultural storytelling. What’s your overarching mission?

Deanna: The overarching mission has always been to create a love letter to America’s forgotten grapes. That’s how we chose the name and approach the storytelling to relate the history. We’re talking to the grapes and apologizing for leaving them behind, while conveying that we see them. Our intent is to bestow the recognition that’s due. This is our springboard for Dear Native Grapes. It’s not just a story but a conversation; we’re learning how these grapes best express themselves in wine or the field, or how these grapes prefer to be fermented and aged. We’ve always framed the project as an experiment with upwards of 30 different varieties in testing; we’re not entirely certain what will do the best in our microclimate yet. Our ethos is never to take any vines out of the land if they don’t perform well, but if it doesn’t thrive, it’s not meant to be at the site.

Alfie: We’re both filmmakers and gravitate towards stories, so when we started learning about these histories of grape growing, especially in the East that were lost to Prohibition, we started asking more questions. Particularly surrounding the loss of diversity in farming, winemaking, and important cultural aspects, we thought: What’s left to salvage? What can we do? We felt compelled to go down this rabbit hole and figure out what that story was. We saw a wealth of knowledge and diversity omitted from America’s cultural fabric during Prohibition. We want to bring this style of heritage wine back to the collective consciousness. The timeliness of the project came at a moment when upcoming pockets of the country are strongly embracing local goods endemic to areas that have inherent value. The project is a larger effort to present heritage wines that carve a space of their own. We’re not trying to make a wine from Concord Grapes that tastes like a vitis vinifera Burgundy because we believe there’s room for something else.

We like the challenge of having conversations with people we meet during tastings who may be unfamiliar with the palates of our wines. Seeing their reactions to the expression of these grape varietals, of which maybe they have preconceived notions about, is great. We have a variety called Niagara that tastes like eating fresh grapes off the vine. To someone who’s used to drinking Pinot Noir from Oregon, yes, this will be very different. But Niagara's a fun wine to drink for different reasons; it doesn’t have to be a complex thing but something that’s enjoyable, and something that’s local to New York. When people try this wine, they’re reminded of their childhood, especially for those who grew up in New England and the Northeast. It connects people to each other.

Deanna: It’s cool for us to see people have this realization––this harkening back to their childhood––in front of us when they try the wine. Knowing that they’ll take the story back to their family is rewarding because it's larger than us. The wine and what it represents continues on a journey of its own, especially in the context of the revitalization of these varietals.

Alfie: We’re trying to spur conversations that heritage grapes are not lesser than European varieties, they’re just different.

Ella: Alfie, you have this massive book that acts as a repository of pre-Prohibition stories and wine-tasting anecdotes. What’s at stake with this project?

Alfie: We’re trying to lay the groundwork for people who are interested in winemaking and can take some of our learnings to replicate grape growing in climates that may have more difficult growing conditions. We’re trying to figure out which grape varietals are hearty and have that be a proof of concept for other winemakers who are interested in the [Catskills] region.

Deanna: It’s funny because when we first moved to Delaware County and were figuring out our intentions, some of the community’s reactions were varied. One person wasn’t optimistic that grapes could be grown at all here, even though they loved the project conceptually. We can’t change everyone’s minds, but we want to embody that actions speak louder than words. The vineyard is alive and thriving, and working. We don’t want to be outliers but encourage others to pursue this as an economic way forward. We live in an area that is economically depressed, so showing others in the community another viable opportunity for farming is important to us and connected to trying to make wine more accessible.

A further extension of our accessibility is our pricing and trying to make our wines affordable to our community; it doesn’t make sense otherwise and would be a failure on our part. We try to have some wines priced lower as a readily accessible product, with some wines in the mid or high price range. Still, these wines fall in the lower price range for everyone. We want to make the work accessible, the project accessible, and the wine accessible.

Ella: Community is a foundational tenet of Dear Native Grapes. How have you built and sustained your community, while continuing to promote the notion that anyone can do this work? How are you working with your local community in your day-to-day operations?

Alfie: We’ve found an awesome community through Instagram just by sharing what we’re up to. Often, we don’t know many of these people in person, although we’ve created strong bonds with them. Small farms and projects doing similar things across the East Coast and in the South have become a well of knowledge for us. A summit on wine, co-ferments, and other natural beverages called “ABV”––Anything but Vinifera––is in its third year to bring producers like us together across all pockets of the country. We get to meet many of our heroes from Wisconsin and Vermont with whom we’ve been talking online. It’s like meeting your best friend for the first time.

Deanna: There’s always a social equity aspect to ABV’s seminars. We too want to be sustainable and understand how we’re impacting the Earth, without erasing Indigenous histories that exist within winemaking or beverage-making that are endemic to other cultures but that we don't really know about here. We want to understand who the overlooked pioneers of this trade and practice are. Deepening the access to land, tools, vines, knowledge and making it more equitable to all people who are interested in this line of work is foundational to Dear Native Grapes.

Alfie: Dovetailing that, greater accessibility for BIPOC folks in winemaking and farming is also important to dilute the elitism in wine. All of these things are crucial to small producers, so when we get together, we discuss new approaches.

Deanna: When people in our community realized that we’re not just producing wine or co-fermenting but actually farming the land and creating a connection to the land as something we’re stewarding and tending, it opened up the community’s eyes. Even if they don’t understand winemaking, they understand farming and land stewardship. When we can meet on those terms, that’s when community starts to form.

Alfie: There’s a practical sense to the community aspect to keep money and currency horizontal within this network of farmers and producers. We try as much as we can to buy locally from our community. Much of our vineyard holistic spray recipes come from local herbs and honey, which are sourced from our friend’s farm from over the hill. All of our farm input materials––compost, wood posts, for example––are sourced from within a 10-mile radius. We try, as much as we can, to contribute to our local community.

Deanna: It’s an opportunity for us to shine a light on other small producers, who also happen to be our friends. We can put their name on the bottle of the grape and honey co-ferment we’re making. We can bond over similar projects to ours to talk to our community about what we’re doing. We don’t have a tasting room or public-facing space, so we’re trying to find other avenues to display our work and elevate what’s possible. It’s not just our business but our home.

Ella: You have no shortage of goals you’re working towards at Dear Native Grapes. What are some of your aspirations for the production and project?

Alfie: There are short-term, medium-term, long-term, and hyper-long term goals. The hyper-long term is to have a Concord wine on the same menu as the upscale Burgundy. To have these wines be part of our culture again and celebrated as our own would be awesome.

Deanna: Short-to-mid-term goal would be to transition into Dear Native Grapes full-time, and leave my current job so this can be sustainable as a source of income for our future family. How do we get to that place? Having a game plan in place to be sustainable in every sense of the word.